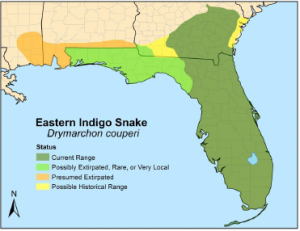

The current distribution of the eastern indigo snake has a reduced geographic area compared to its historic range (Figure 6). Enge et al. (2013, entire) described current extant populations (records post year 2000) to occur in much of its historical range in Georgia and Florida but records are lacking or scarce in portions of that range. Eastern indigo snakes are extirpated or are very rare in the Florida Panhandle and Southwest Georgia. Naturally occurring populations are probably no longer extant in Alabama and Mississippi based on lack of recent records (Enge et al. 2013, p. 296). As part of the current recovery strategy, repatriation of eastern indigo snakes back into former parts of its range is ongoing in Alabama and the Florida Panhandle (see section 4.8 below). In summary, the majority of recent records for the eastern indigo snake are from southeastern Georgia and peninsular Florida. The eastern indigo snake may persist in the panhandle of Florida, but only in low numbers.

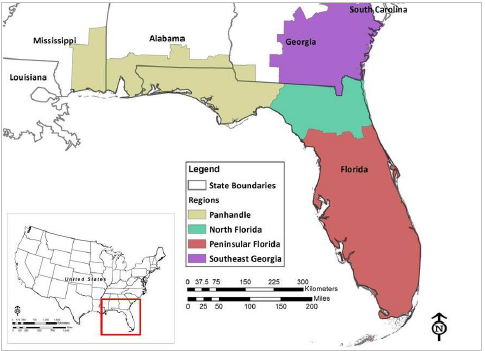

We divided the distribution of the eastern indigo snake into the following four regions: the Panhandle, North Florida, Peninsular Florida and Southeast Georgia (Figure 7). These regions were delineated along state and county boundaries that represent the geographic (east-west and

17 north-south) distribution of the species. This geographic distribution represents the both the ecological and genetic diversity of the species. Eastern indigo snake behavior, such as home range size, movement and dependence on gopher tortoise burrows for cool-season shelter has been documented to vary across a north to south gradient likely due to climatic differences (Hyslop et al. 2009a, entire, Bauder et al. 2018, entire). The Panhandle, North Florida and Southeast Georgia regions all represent the “northern populations” and Peninsular Florida represents the “southern populations.” The north-south gradient also represents a genetic gradient described by Folt et al. (2019). Southeast Georgia and North Florida regions generally align with the Atlantic-Gulf (east-west) genetic gradient described by Krysko et al. (2016a,b). The Panhandle region represents the western portion of the species range and is disjunct from the eastern regions because of the paucity of recent eastern indigo records due to habitat degradation and losses of gopher tortoise populations from harvest for human food (Enge et al. 2013, p. 289). The North Florida region geographically connects the east-west and north-south regions. This regional breakdown provides a framework to assess the species’ ecological and genetic diversity (representation).

For each region we mapped the number of eastern indigo snake records to depict the known distribution of the species. Records are element occurrence data collected over time (a few very early 1800’s records, but most records occurred between the years 1936-2017). These records are documented as geographic coordinates (latitude, longitude) that can be displayed in a Geographic Information System (GIS) and represent unique observations of eastern indigo snakes at specific locations on specific dates in time. Range-wide species occurrence data used in this report are from Enge et al. (2013, entire), which includes records up to the year 2012. Post 2012 to 2017 records were obtained directly from State Natural Heritage Programs, State Herpetologists and conservation organizations in Florida and Georgia. It is important to note that survey and monitoring efforts are not evenly distributed across the range. The number of records varies across the range with some areas having many records from research and monitoring efforts to other areas having no or few records which could represent lower numbers of snakes or that the area is under-surveyed. In addition, records may represent the same individual snake documented at multiple points in time. Numerous records are from observations on roads (dead or alive). The “heat maps” that are provided for each region in the following section show where we know the species to have occurred historically compared to current. Current distribution is represented by records from 2001-2017, similar to the distribution described by Enge et al. (2013, entire). A total of 2,272 records were used in this report, of which about half (1,239) are considered current. See section 5.1 below for more detail on how records are used in this report.

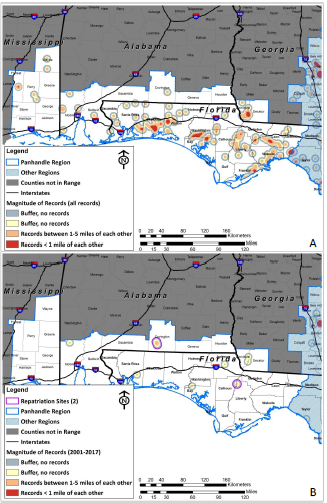

2.4.1 Panhandle

The Panhandle represents the western-most distribution of the species and includes extreme south Alabama and southeastern Mississippi, the Florida Panhandle (west of the Aucilla River in Florida) and two southwestern counties in Georgia (Figure 8). This region has experienced significant declines in eastern indigo snake populations and the species is believed to be extirpated in Alabama and Mississippi, and very rare in the Florida Panhandle.

Alabama

Four historical (1954 or earlier) eastern indigo snake records are known from three counties in Alabama (Covington (Neil 1954), Baldwin (Haltom 1931) and Mobile (Löding 1922) counties) (Enge et al. 2013, p. 294). Three additional recent records are reported from Mobile County in 2000 and 2001; however these records are Type II records (Enge et al. 2013, p.290) and are not supported by photos or specimens (see section 5.1). It is possible, though, that the species was more abundant than former records indicate because herpetologists studying the reptiles of Alabama in the early 1900’s did not mention that eastern indigo snakes were rare (Blanchard 1920, Löding 1922). Nevertheless, by the mid-1970’s herpetologists were concerned that the species had disappeared from Alabama (Mount 1975).

In an effort to repatriate the species, 537 eastern indigo snakes (adults, juveniles, and hatchlings) were released at about 20 sites across Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina beginning in 1976 and continuing through 1987 through a project conducted by Auburn University (Speake 1990, entire). A captive breeding colony at Auburn University was used to produce snakes for the repatriation efforts (Speake 1990, entire). A preliminary assessment of survival of released snakes was conducted from 1986 through 1989; captures or sightings of eastern indigo snakes occurred at five of the 16 release sites evaluated (Speak 1990, entire). No recent records of eastern indigo snakes are known from these areas and the repatriation effort is considered unsuccessful (Hart 2002, Irwin et al. 2003, Smith et al. 2006, Stevenson et al. 2008). In 2002, a study was completed in Alabama to determine if evidence of the species could be verified (Hart 2002). In 2000, sites of experimental repatriation from the 1980s (Hart 2002) were visited and landowner contacts were made. In addition, recent anecdotal sightings and reports were researched and attempts made to determine their accuracy; none could be verified as eastern indigo snake records. No eastern indigo snakes were observed by Hart (2002) during the study, and he concluded that if eastern indigo snakes still occur in Alabama, they occur at such low densities that detection is improbable.

In 2010 an eastern indigo snake repatriation project was launched at a site located on the Conecuh National Forest (CNF), Covington County, Alabama (Godwin et al. 2011). Thirty-eight eggs of wild-caught gravid females from southeastern Georgia were hatched and reared in captivity through approximately two years of age (until they reached a size of 3 to 4 ft (0.97 to 1.22 m)) and released on the CNF. These 38 snakes were intensively monitored via radio telemetry during 2010-2011 and 13 were reported to have died, 12 were not relocated, and 13 were reported alive at the conclusion of the study. Mortality was due to a combination of vehicular strikes, predators and unknown factors (Godwin et al. 2011, entire). The first indication that this reintroduction may prove to be a success is evidence of successful breeding at the site; two females tracked via radio telemetry were captured in 2012, laid eggs that produced nine offspring (Stiles et al. 2013, p. 40). Since 2011, 116 additional snakes have been released (154 total) on the CNF most of them reared at the Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation (OCIC), located in central Florida. Post radio telemetry monitoring, at least 10 confirmed observations of eastern indigo snakes near the release sites have been reported between 2012-2018 (Godwin 2018). No unmarked eastern indigo snakes have been captured, which would be an indicator of survival of offspring from repatriated snakes (Stiles et al. 2013, p. 40). Over the next five to seven years at CNF, it is anticipated that about 150 more snakes will be released at the CNF to reach a target of about 300 snakes released (Godwin and Steen 2017, entire).

Mississippi

Cook (1954) reported three specimens from Mississippi; one specimen is in the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science collected from Wayne County, Mississippi in 1939. The most recent credible record for the species in this state is from two eastern indigo snake sightings reported from the mid-1950’s on DeSoto National Forest, Perry County, Mississippi (C. Finch, Governor of state of Mississippi in litt. 1977, Lohoefener and Altig 1983) and a 1955

20 observation from Forrest County. Due to the lack of confirmed recent records for the eastern indigo snake in Mississippi, it is likely extirpated in the state.

Florida Panhandle

The Florida Panhandle includes counties that are west of the Aucilla River. While the species is known throughout Florida, few or no recent records exist from the panhandle (Gunzburger and Aresco 2007, Enge et al. 2013, p. 292). In the 1980’s, Moler (1985a) conducted a distributional survey of the eastern indigo snake in Florida by compiling records from 32 institutions and obtaining sightings from interviews with 95 biologists and other individuals familiar with the species. Museum specimens were available from 44 counties and sightings from 63 of Florida’s 67 counties. Moler (1985a) concluded that the eastern indigo snake was “distributed widely, though not necessarily commonly throughout Florida, including the panhandle.” Enge et al. (2013) documented 578 recent (2001–2012) eastern indigo snake records from 47 counties in Florida, however, they concluded that eastern indigo snakes are now rarely observed and have a restricted distribution in the Florida panhandle. The most recent verifiable eastern indigo snake record for the region was at Eglin Air Force Base in 1999; a credible (but not verified by photo or specimen) eastern indigo snake sighting was reported from close to the Base boundary in 2011 (Enge et al. 2013). The decline of eastern indigo snakes in this region may have resulted from a dramatic decline in gopher tortoise populations, going back to the mid 1900’s and coinciding with a period of heavy human predation on tortoises. In 2017, a repatriation project was launched at the Nature Conservancy’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve in Liberty County where 32 snakes were released in 2017-2018, with future releases planned. Prior to this, the last confirmed eastern indigo snake on the Preserve was in 1982.

In extreme southwestern Georgia (Decatur and Seminole counties) at least one small population may still occur. This population is close to the Florida state line and may be a northerly extension of the Florida population inhabiting the sandhills along the Apalachicola River (Enge et al. 2013, p. 297); therefore, is included as part of the Panhandle region described in this report.

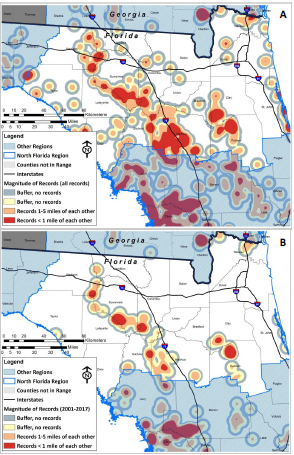

2.4.2 North Florida

The North Florida region includes counties east of the Aucilla River (Jefferson County) and north of the latitude of Gainesville, Florida, where the eastern indigo snake is dependent on gopher tortoise burrows for overwintering shelter (Enge et al. 2013, p. 297) (Figure 9). A total of 222 records are reported for this region with 83 recent records (2001-2017) (Enge et al. 2013 and unpublished data). While once widely distributed across this region, recent eastern indigo snakes sightings are mostly documented in upland areas along the Suwannee River in Alachua, Columbia, Gilchrist, Lafayette, and Suwannee counties. Eastern indigo snakes are also recently documented in Clay and Putnam counties, including on Camp Blanding Joint Training Center and Etoniah Creek State Forest. A few records are from the coastal areas in this region, such as Guana River Wildlife Management Area. This region links the western region (Panhandle) where recent eastern indigo snake records are very rare and the north (Southeast Georgia) and south (Peninsular Florida) regions where the majority of recent records occur. This region represents the only part of Florida that currently supports “northern” populations of eastern indigo snakes.

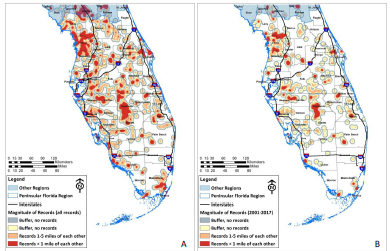

2.4.3 Peninsular Florida

The Peninsular Florida region includes central and south Florida counties south of the latitude of Gainesville, Florida where eastern indigo snakes are less dependent on gopher tortoise burrows for overwintering shelter (Figure 10). A total of 1,107 records are reported for this region with 533 recent records (2001-2017) (Enge et al. 2013 and unpublished data). Eastern indigo snakes remain widespread and more commonly observed in central and south Florida, except for parts of the urbanized southeastern coast in Palm Beach and Broward counties. In the peninsula, they are more widely distributed, across different habitat types, than in other parts of their range although they continue to prefer upland habitats (Bauder et al. 2018). They are known from the Ocala area where they are widely distributed but not common. Eastern indigo snakes are also widespread in the Osceola Plain and along the Lake Wales Ridge on large unfragmented habitats (including large ranchlands) (Enge et al. 2013, p. 293). Given the species’ preference for upland habitats, eastern indigo snakes are not commonly found in the wetland complexes of the Everglades region even though they have been found in pinelands, tropical hardwood hammocks, and mangrove forests in extreme south Florida (Duellman and Schwartz 1958, Steiner et al. 1983, Metcalf 2017). Eastern indigo snakes occur on some islands in Florida. Along the Atlantic Coast, populations occur on Merritt Island in Brevard and Volusia counties. Along the Gulf Coast in Lee County, the species still occurs on Cayo Costa, North Captiva, Big Pine, and Little Pine islands, but the population on the more developed Sanibel Island may have been extirpated (Enge et al. 2013, p. 293). Historically, the eastern indigo snake also occurred across the Florida Keys from Key Largo to Sugarloaf Key. The species may persist on Little Knockemdown Key (validated sighting in 2009 and a skeleton found in 2018), but the species is likely extirpated from most of the Keys.

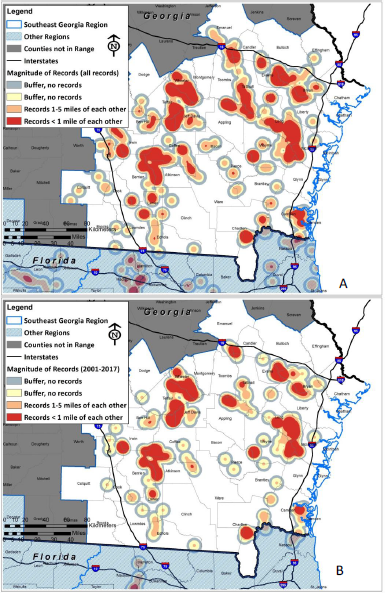

2.4.4 Southeast Georgia

In Georgia, the first extensive effort to survey the distribution of the eastern indigo snake, as well as characterize and delineate its habitat, was conducted by Diemer and Speake (1983) between 1978 and 1980. Results of this study indicated that the stronghold for the snake was in a contiguous block of approximately 41 southeastern and south-central Georgia counties. Undeveloped sand ridges of coarse white sands lying along the northeastern sides of blackwater streams in the Atlantic Coastal Plain are prime eastern indigo snake habitat (Stevenson et al. 2008, p. 340). In a recent review completed by Enge et al. (2013), the eastern indigo snake was found to remain widespread in the lower and middle Coastal Plain of southeastern and south-central Georgia and it is regularly observed in sandhill habitats along the major river systems in this area (Figure 11). A total of 763 records are reported for Georgia with 614 recent (2001–2017) records for 29 Georgia counties (Enge et al. 2013 and unpublished data). However, recent records (2001-2017) indicate that the range has contracted to south of Interstate 16 and east of Interstate 75 (Figure 11), except for a recent record just west of Interstate 75 near Reed Bingham State Park (Enge et al. 2013, p. 291). Despite localities mapped by Diemer and Speake (1983) based upon “credible sightings,” the occurrence of eastern indigo snakes in the following areas of Georgia has never been substantiated by photographs or specimens: (1) the Fall Line Sandhills region, including the Ft. Valley plateau; (2) the Fall Line Red Hills; and (3) the Tallahassee Hills (i.e. Tallahassee Red Hills) (physiographic regions follow Wharton 1978). Records are absent from the Savannah area in Chatham County, although suitable habitat occurs (at least historically) in the form of xeric sandhills along the Ogeechee River. Valid records are also lacking from any barrier island in Georgia. From Glynn County northward, records are absent from the coastal province adjacent to the mainland coast except for a single, old record for Glynn County (no date, no precise locality data, labeled from “Brunswick,” not mapped in Figure 11). The historic and current status for upland islands within the interior of the vast Okefenokee Swamp is poorly known; there are old, credible sightings but no recent records (Diemer and Speake 1983, Stevenson 2006, Enge et al. 2013).