2.5.1 Life History

Reproduction and Development

Although the eastern indigo snake is a diurnal (active during the day) species (Stevenson et al. 2008) it is not amenable to standard population survey and mark/recapture methods like most snake species (Steen 2010, entire), and a robust, inexpensive survey technique has not been found (Enge 1997, Smith and Dyer 2003, Stevenson et al. 2003 p. 394, Alessandrini 2005, Ford and Ford 2005, Bolt and Weiss 2006, Mason et al. 2007, Stevenson et al. 2009, Hyslop et al. 2009b, Stevenson et al. 2010b, Rothermel 2017, p.15). However, even though the eastern indigo snake is difficult to consistently locate in the field we have learned important life history characteristics from numerous studies.

Several estimates of sex ratios are documented from studies on wild populations. Three studies of hatchlings/juveniles (Moulis 1976, Steiner et al. 1983, Godwin et al. 2011, p. 32) reported sex ratios not differing from 1 male to 1 female. However, it appears that sex ratios become more male biased in adult snakes. Layne and Steiner (1996) reported an adult sex ratio of 1.54 males to 1 female for eastern indigo snakes in south Florida. Stevenson et al. (2009) reported a ratio of 2.1 males to 1 female (63 males, 29 females), with no significant difference in recapture rates between sexes, in a study at Fort Stewart, Georgia. Maturity in wild snakes has been estimated to be attained at about 5.0 ft (1.52 m) total length (Speake et al. 1987, Layne and Steiner 1996).

Eastern indigo snakes breed during the autumn and winter months, October through February. Males are often aggressive during this time competing for mates (Figure 12). Few nest sites have been observed but they have been found in open-canopied sandy habitats associated with gopher tortoise burrows (Stevenson et al. 2008, p. 340, Newberry et al. 2009, p. 97). Hyslop (2009a, p. 461) found females using upland sandhills in early spring, after males had mostly dispersed to lowland habitats, specifically using a higher proportion of abandoned gopher tortoise burrows during what was assumed to be just prior to nesting. Some reproductive data can be gleaned from captive populations. Speake et al. (1987) reported that two females, captive since birth, bred at 40 and 41 months of age (about 3.5 years). The clutch size of 21 females, removed from the wild and laying eggs in the spring following their capture ranged from 6 to 12 (average = 8.5), number of hatchlings ranged from 0 to 11 and clutch viability ranged from 0-100% (Godwin et al. 2011, pp. 25-26). Moulis (1976) reported a range of 4 to 12 eggs for captive females and estimated their sexual maturity to be reached at 3 to 4 years of age based on their rate of growth. Captive female eastern indigo snakes typically lay eggs between April and June that hatch in August to September. Several studies indicate that annual reproduction is possible. Speak et al. (1987) reported 20 of 21 females captured during the spring were gravid and Hyslop (2007) reported that all females (9) examined in the spring were gravid. In a two-year study of a wild population, 3 of 5 females studied were gravid in both years (Bolt 2006). Eastern indigo snakes hatched in captivity are on average 1.4 ft (41.2 centimeters (cm)) and grow to about 2.6 ft (79.5 cm), 3.7 ft (113.9 cm), and 4.0 ft (121.9 cm) by years 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Hoffman 2018). Twelve individuals recaptured in Georgia indicate faster growth rates for subadult and small adult snakes than for large adults (Stevenson et al. 2003, p. 397). The lifespan of eastern indigo snakes is not well-understood. The maximum reported longevity for a captive eastern indigo snake of unknown sex was 25 years and 11 months (Shaw 1959); a study of wild eastern indigo snakes in Georgia reported that individual snakes often reach ages of 8 to 12 years (Stevenson et al. 2009).

Diet

The diet of the eastern indigo snake reflects the species’ large home range and movement between uplands, lowlands, and other landscapes in which it occurs. The eastern indigo snake is an active forager (Stevenson et al. 2008, p. 341) seeking out its prey rather than sitting and waiting on its prey. A review of prey records indicates that the eastern indigo snake consumes a wide variety of animals, but the primary prey are rodents, anurans, snakes and small turtles (Stevenson et al. 2010a). While eastern indigo snakes depend on gopher tortoises for their burrows they are also known to eat small tortoises (Stevenson et al. 2010a, p.3). In south Florida, eastern indigo snakes have been documented to consume non-native species such as a walking catfish (Clarius batrachus) (Metcalf and Herman 2018, p.341) and a hatchling Burmese python (Python bivittatus) (Andreadis et al. 2018, pp.341-342). Nevertheless, more than half of the 47 different vertebrate prey species documented by Stevenson et al. (2010a, p.6) were snakes, including venomous snakes (Figure 13) and other eastern indigo snakes.

Home Range and Movement

Adult eastern indigo snakes have very large home ranges; most estimates of home ranges vary from several hundred to several thousand acres (ac) (tens to over a thousand hectares (ha)) (Speake et al. 1978, Moler 1985b, Dodd and Barichivich 2007, Hyslop 2007, Breininger et al. 2011, Hyslop et al. 2014, Jackson 2013, Metcalf 2017, Bauder et al. 2018). On average the home ranges of adult male eastern indigo snakes are substantially larger than the home ranges of adult females (Appendix A). Male and female eastern indigo snake home ranges are considerably larger compared to other large North American snakes such as those summarized by Hyslop et al. (2014, p.107): the eastern coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum) < 250 to 450 ac (<100 ha to 183 ha), snakes of the genus Pituophis (Pine and Bullsnakes) averaged 195 ac (79 ha), the eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) male home ranges are between 69 and 197 ac (28 and >80 ha) and the timber rattlesnake male home range averaged around 276 acres (112 ha).

Movement between habitat types varies between northern and southern portions of the species’ range, possibly based on location above and below the frost line (near the latitude of Gainesville, Florida) and a need for more winter protection from the cold above the frost line. In the more northern parts of the species’ range (i.e., Georgia and North Florida), habitat use often varies seasonally between upland and lowland areas, especially where the snakes habitually overwinter in gopher tortoise burrows in xeric sandhill habitats (Hyslop et al. 2009a). Northern winter home ranges tend to be small (less than 25 ac (10 ha)), in spite of evidence of breeding activity, when compared to home ranges in spring through autumn (up to 3,700 ac (1,500 ha)) when more diverse habitats are occupied (Speake et al. 1978, Stevenson et al. 2009, Hyslop et al. 2014). In more southern parts of their range in Peninsular Florida, eastern indigo snakes become more habitat generalists and move among the available habitat types but maintain a strong affinity to upland habitats (Bauder et al. 2016b, Bauder et al. 2018). Unlike in northern regions, male eastern indigo snakes take longer, more frequent movements and have larger home ranges during the winter breeding season, although both male and female home ranges tend to be smaller overall than those in the north (Bauder et al. 2016b, p.221). A comparison of Peninsular Florida mean annual home range size with mean annual home range size in Southeast Georgia, using data from Hyslop et al. (2014), is described in Bauder et al. (2016b, p.223): male home range of 369 ac (149 ha) in Peninsular Florida versus 1,260 ac (510 ha) in Southeast Georgia; female home range of 121 ac (49 ha) in Peninsular Florida versus 252 ac (102 ha) in Southeast Georgia. A comparison of annual home range data for eastern indigo snakes collected in specific locations from various studies using radio telemetry to track snake movements is provided in Appendix A.

In addition, Peninsular Florida movements reported in Bauder (et al. 2016b, p.223) did not indicate seasonal movements between winter and summer habitats as described for Southeast Georgia (Hyslop et al. 2014). Home range overlap of male and female eastern indigo snakes in Peninsular Florida was significantly greater than overlap between individuals of the same sex, although female home ranges overlapped more frequently in the nonbreeding season (Bauder et al. 2016a, p.221). Male home ranges often completely encompassed female home ranges but rarely overlapped each other (Bauder et al. 2016a, p.221). A somewhat different pattern was described by Hyslop et al. (2014) for eastern indigo snakes in Southeast Georgia. All eastern indigo snake home ranges in that study overlapped those of multiple other eastern indigo snakes and the two largest male home ranges overlapped each other year-round (Hyslop et al. 2014).

Adult eastern indigo snakes, especially males, can move considerable distances. An adult male in Georgia was recaptured over 13.5 miles (mi) (22 kilometers (km)) linear distance from its original capture (Stevenson and Hyslop 2010, entire), but maximum long distance linear movements for males of 3-5 mi (5-8 km) are more common (Hyslop et al. 2014, p. 105). In central Florida long range distance linear movements are shorter than recorded in Georgia. An adult male in central Florida was recorded to travel 4.3 mi (7 km) (Breininger and Bolt unpublished data), but maximum long distance linear movements of about 2.4 mi (3.9 km) are more common (Bauder et al. 2018 p. 747). Large home ranges and long distance movements indicate that the species is especially vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and road mortality (Breininger et al. 2004, Breininger et al. 2011, 2012; Hyslop et al. 2011, Hyslop et al. 2012). Large areas of natural habitats, protected from roads and the fragmentation associated with development are needed to maintain viable snake populations (Layne and Steiner 1996, Breininger et al. 2004, Dodd and Barichivich 2007, Breininger et al. 2011, 2012; Hyslop et al. 2012, Enge et al. 2013).

2.5.2 Habitat

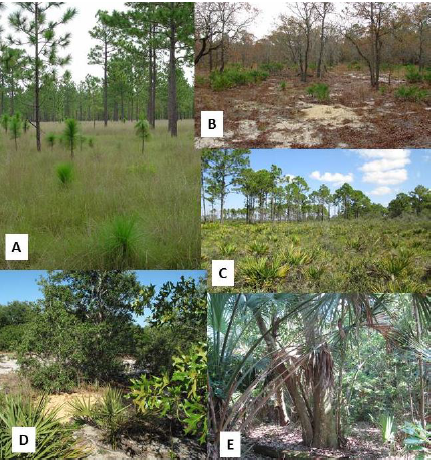

The eastern indigo snake occurs in a wide range of upland and lowland habitat types including mesic pine flatwoods, scrubby flatwoods, longleaf pine sandhills, oak scrub, sand pine scrub, dry prairie, tropical hardwood hammocks, freshwater and saltwater marshes and swamps, coastal dunes, and some human-altered habitats (USFWS 1982, Moler 1992, Stevenson et al. 2008, Hyslop et al. 2009a, Enge et al. 2013) (Figure 14). They may move seasonally between upland and lowland habitats, especially in northern portions of their range. However, across its range eastern indigo snakes exhibit a strong preference year-round for upland habitat types (Bauder et al. 2018 pp. 754-755, Hyslop et al. 2014, p. 108)).

Throughout their range, eastern indigo snakes may also use below-ground shelter sites for refuge, breeding, feeding and nesting (Speake et al. 1978, Stevenson et al. 2003 p. 395, Hyslop et al. 2009a, Stevenson et al. 2010b). In the northern part of their range, burrows are used to protect against the cold. In summer, eastern indigo snakes use burrows as protection from heat and dry conditions since they have been shown to be susceptible to desiccation (Bogert and Cowles 1947). Reliance on xeric sandhill habitats throughout the northern portion of the eastern indigo snake’s range in Georgia and northern Florida is due to the dependence on gopher tortoise burrows for shelter during winter (Stevenson et al. 2003 & 2009, Hyslop et al. 2009, Bauder et al. 2017, p. 78) (Figure 15). However, presence of gopher tortoise burrows alone is not a sufficient predictor of suitable overwintering habitat for eastern indigo snakes (Bauder et al. 2017, p. 78). Eastern indigo snakes use both active and inactive gopher tortoise burrows. In Georgia, eastern indigo snakes have been documented to have den site fidelity, returning to the same sandhills and sometimes the same burrows over multiple winters (Stevenson et al. 2003 p. 401, Hyslop et al. 2009a p 460, Hyslop et al. 2017 p. 105). In wetter habitats that lack gopher tortoises, eastern indigo snakes may take shelter in hollowed root channels, hollow logs, stump holes, or the burrows of rodents, armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), or land crabs (Cardisoma guanhumi) (Lawler 1977, Moler 1985b, Layne and Steiner 1996, Hyslop 2007, Hyslop et al. 2009a). Juvenile and subadult eastern indigo snakes are very difficult to detect in the wild, thus there is a poor understanding of the ecology of these age classes. In Georgia Hyslop et al. (2009b, p. 97) captured 4 subadults, including a hatchling, using box traps. Bauder et al. (2012, p. 343), observed 13 juvenile snakes in the xeric sandhills of Georgia and suggest that lower detection rates of juveniles may be due to more cryptic behavior, low densities, and rare use of gopher tortoise burrows as shelter because of the threat of cannibalism.

Throughout Peninsular Florida, the eastern indigo snake may be found in almost all terrestrial habitats except in areas with high-density urban development (Moler 1992, Enge et al. 2013). From the latitude of around Gainesville, Florida, south, they are less tied to longleaf pine sandhills and become more habitat generalists, although they still require below-ground shelter sites and commonly use gopher tortoise burrows and sandy xeric habitats when these are available (Layne and Steiner 1996, Enge et al. 2013, Bauder et al. 2016b). Eastern indigo snakes can be common in some hydric hammocks (Moler 1985a, Bauder et al. 2018). On the sandy central ridge (i.e., Lake Wales Ridge) of south Florida, eastern indigo snakes may use gopher tortoise burrows more (62 percent) than other underground shelter (Layne and Steiner 1996). In extreme southern Florida, they are typically found in pine flatwoods, pine rocklands, tropical hardwood hammocks, and in most other undeveloped areas (Kuntz 1977, Enge et al. 2013). Below-ground shelter sites used in these areas include burrows of armadillos, hispid cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus), and land crabs; burrows of unknown origin; natural ground holes; hollows at the base of trees or shrubs; ground litter; trash piles; and crevices of rock-lined ditch walls (Layne and Steiner 1996).

Eastern indigo snakes are also known to utilize human-altered habitats. In Florida, agricultural sites, such as sugar cane fields, improved pasture sites, citrus groves, and canal banks created in drained wetland areas are sometimes occupied by eastern indigo snakes (Enge et al. 2013, O’Bryan 2017 p. 1, Bauder et al. 2018 p. 756). Additional habitat photos are provided in Appendix A.